PFAS Federal Legislation in the 116th Congress

State Impact Center / January 19, 2019

Updated January 19, 2021.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are bioaccumulative and environmentally persistent, have been widely used in commercial applications since the 1950s and have been linked to a series of human health harms, including cancer, kidney disease and birth and developmental disorders. The chemicals have been detected in the drinking water of more than six million Americans at a level exceeding the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) 2016 lifetime drinking water health advisories level of 70 parts per trillion (ppt) — a level seven to ten times greater than the safe level of exposure estimated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2018.

The widespread public exposure to dangerous levels of PFAS chemicals in drinking water and other potential pathways has triggered significant concern in Congress. Congressional concern has not been allayed by the EPA’s release of a PFAS “Action Plan” in February 2019 or subsequent actions the agency has taken, including final interim recommendations to address groundwater contaminated with perfluorooctanic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) chemicals and a supplemental notice of proposed rulemaking to promulgate a significant new use rule for long-chain PFAS chemicals under the Toxic Substances Control Act.

During the 116th Congress (2019-2021), Congress used the annual processes around the Department of Defense’s authorization bill (the National Defense Authorization Act or “NDAA”) and government-wide appropriations bills to adopt PFAS-related programs and provisions. The 2019 and 2020 NDAA and appropriations processes are discussed below as are the many pieces of stand-alone PFAS legislation that were introduced in the 116th Congress. The stand-alone legislation encompassed four legislative focal areas four legislative focal areas: (1) enhanced detection and research; (2) new regulatory mandates; (3) cleanup assistance; and (4) exposure to PFAS contamination at or near military installations. Information on PFAS legislation in the current 117th Congress (2021-2023) can be found here.

2020 NDAA, WRDA and Appropriation Bills

Attorneys General Action

In October 2020, Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel led a coalition of 20 attorneys general in sending a letter to Congress about the states’ PFAS-related priorities for the enacted-version of the fiscal year 2021 NDAA. The letter requested that the conference report include the provision in the House-passed fiscal year 2021 NDAA (H.R. 6395) that would require DOD to meet or exceed the most stringent cleanup standard for PFOS or PFOA contamination between an enforceable state standard under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA or the Superfund statute), an enforceable federal standard under Superfund or a health advisory under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) from DOD or National Guard activities found in drinking water or in groundwater that is not currently used for drinking water.

The attorneys general also requested that final version of the fiscal year 2021 NDAA include other provisions in the House’s fiscal year 2021 NDAA, such as additional funding and authorization for PFAS cleanup, robust resources for ongoing and new studies, and alternatives to firefighting foam containing PFAS. Additionally, the letter asked that provisions from the House bill to require DOD to offer PFAS blood testing for all interested service members as part of their routine physicals and limiting the PFAS-containing products the Defense Logistics Agency may procure be included in the enacted-version of the fiscal year 2021 NDAA.

The letter also encouraged Congress to act to regulate PFAS chemicals, including designating them as a hazardous substance under the Superfund statute.

The conference report for the fiscal year 2021 NDAA (below) unfortunately did not include most of the provisions that the attorneys general had pushed to be included in the final NDAA for the year. But the bill did include a prohibition on DOD procuring items containing PFAS chemicals, including cookware, carpets and upholstery with stain-resistant coating as requested by the attorneys general. The fiscal year 2021 NDAA cleared the House and Senate in December 2020 and is headed to the President’s desk.

National Defense Authorization Act

On December 4 2020, the House and Senate Armed Services Committee released the conference report for the fiscal year 2021 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). On December 8, 2020, the House passed the conference report for the bill with a veto-proof margin, and the Senate did the same on December 11, 2020. On December 23, 2020, the President vetoed the bill over issues unrelated to PFAS chemicals. On January 1, 2021, the Senate, after the House had earlier done the same, overrode the veto and the fiscal year 2021 NDAA became law.

The NDAA annually authorizes Department of Defense (DOD) programs, and includes several PFAS-related provisions because significant PFAS contamination of water supplies has been identified at or around a number of military installations. The conference report resolves the differences in the respective versions of the House- and Senate-passed fiscal year 2021 NDAAs.

In general, the final legislation includes lower funding levels for PFAS programs than had been included in the House’s version of the fiscal year 2021 NDAA that had passed in July 2020. The bill authorizes $1.4 billion for environmental remediation at DOD facilities. The legislation also authorizes $90 million for research that supports the development of PFAS remediation and other PFAS-related technologies, and the final package includes $15 million for a CDC study of the health implications of PFAS contamination in drinking water.

A couple of PFAS-related policy proposals in the House’s fiscal year 2021 NDAA were not included in the conference report. Stripped from the final bill was the provision in the House bill that would have required DOD to meet or exceed the most stringent federal or state cleanup standard for PFOS or PFOA groundwater contamination. Meeting a similar fate was a provision that would have required DOD to publish on a public website the results of drinking water and groundwater PFAS testing conducted on military installations or former defense sites and a requirement that manufacturers disclose all discharges of over 100 pounds of PFAS chemicals listed on the Toxics Release Inventory.

As was the case with the prior year’s NDAA, Congress remains concerned about the use of firefighting foam containing PFAS chemicals at DOD facilities, which must be phased out by October 2024. Included in the fiscal year 2021 NDAA is the requirement that DOD survey and report on firefighting agent technologies that will help facilitate the phaseout and establishment of a prize that can be awarded by DOD for innovative research that results in a viable replacement agent for firefighting foam that does not contain PFAS. DOD will also be required to notify all agricultural operations within 10 square miles of a location where covered PFAS has been detected in groundwater that is suspected to originate from use of firefighting foam on a military installation.

Lastly, similar to a provision in the House bill, the final package prohibits DOD from procuring items containing PFAS chemicals, including cookware, and carpets and upholstery with stain-resistant coating.

WRDA

Congress regularly enacts an updated Water Resource Development Act to authorize U.S. Army Corps of Engineers water infrastructure projects and activities, often on a biennial cycle. With the last WRDA enacted in 2018, 2020 presents an opportunity for Congress to pass a WRDA with PFAS-specific provisions.

There had been some optimism that a WRDA with PFAS provisions could be enacted in 2020 after the House passed its Water Resources Development Act of 2020 (WRDA) (H.R. 7575) on July 29, 2020 that included some PFAS-specific language. But on December 8, 2020, the House passed a stripped down version of WRDA legislation (S. 1811) that did not include any PFAS provisions, signaling that Congress would not move WRDA with PFAS-specific provisions in 2020. The House passed the stripped down WRDA bill in amended form from an earlier version of the bill that the Senate had passed in July 2019, which means that the Senate would have to pass S. 1811 once again in order for the legislation to become law. S. 1811 was included, without PFAS-related provisions, in the fiscal year 2021 government spending bill (below).

Appropriation Bills

On December 21, 2020, both the House and Senate passed the appropriations spending package for fiscal year 2021, which included several PFAS-related provisions. The legislation was signed into law by President Trump on December 27, 2020.

The EPA portion of the bill includes funding for many PFAS programs. The bill provides $20 million to states to address PFAS contamination through treatment, remediation and cleanup.

The agency is urged to expeditiously remediate Superfund sites contaminated by these emerging contaminants, including PFAS chemicals, and to provide technical assistance and support to states during the cleanup process.

The legislation includes a little over $44 million to the agency for priority actions under the PFAS Action Plan, an increase of $17 million over the fiscal year 2020 enacted level. The legislation also urges the EPA to expeditiously establish a maximum contaminant level (MCL) for PFAS chemicals under the Safe Drinking Water Act as called for in the PFAS Action Plan and requires the agency to brief the House and Senate Appropriations Committee within 60 days on its progress on establishing the MCL.

The final spending package continues the $2 million in base funding that was included in fiscal year 2020 for the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry’s work on PFAS chemicals and other contaminants of emerging concern and contains $2.7 million for the U.S. Geological Survey for research on PFAS transmission in watersheds and aquifers.

The Military Construction/Veterans Affairs component of the final spending package includes $100 million more than as requested by the Trump administration’s fiscal year 2021 budget proposal for cleanup at military installations affected by PFOS and PFOA contamination. Funding cleanup at military installations at this level nearly split the difference in the House’s appropriations bill that would have provided $200 million more in funding for PFOS and PFOA cleanup and the Senate bill that would have only provided an additional $7 million in cleanup funds.

The DOD division of the final appropriations bill includes a number of PFAS provisions. The bill provides DOD an increase of more than $45 million over the budget request from base operations support funding for PFAS chemical remediation at DOD facilities. The bill also includes $51 million more than as requested in the Trump administration’s final proposed budget for technology research on the remediation, disposal, replacement, and cleanup of PFAS chemicals. The DOD award for innovation research that results in a replacement agent for firefighting foam that does not contain PFAS chemicals, which was established in the fiscal year 2021 NDAA (above), received a plus up of $5 million. Lastly, DOD is directed within 180 days of enactment of the legislation to brief the House and Senate Appropriations Committees on the replacement firefighting agent research efforts.

The spending package for the Department of Education includes a PFAS item. The legislation provides the Centers for Disease Control with $1 million for awarding of grants to develop voluntary training courses for health professionals to understand the potential health impacts of PFAS exposure.

The part of the bill with funding for the Department of Agriculture also includes a number of PFAS-related provisions. First, as in the Senate’s version of their appropriations package, the Department is directed to use the Dairy Indemnity Payment Program to purchase and remove PF AS contaminated cows from the market. Similarly, the Food and Drug Administration is directed to determine whether food packaging with PFAS chemicals continues to meet the safety standards of a reasonable certainty of no harm under intended conditions of use.

2019 NDAA and Appropriation Bills

Attorneys General Action

State attorneys general have requested, or filed suits to require, that the EPA and other federal agencies and departments take steps to cleanup PFAS contamination. In July 2019, New York Attorney General Letitia James led a coalition of 20 attorneys general in sending a letter to Congress discussing states’ immediate legislative needs to respond to PFAS contamination. It urged Congress to take legislative steps similar to many of the PFAS-related legislative provisions referenced below, which are currently before Congress through the appropriations process, DOD authorization legislation or as stand-alone legislation.

The following month, August 2019, Pennsylvania Attorney General Joshua Shapiro sent a letter to congressional leaders to urge Congress to move quickly to enact legislation to address the critical need to regulate PFAS chemicals. The letter requested that Congress support several provisions in the Senate and House versions of the National Defense Authorization Act, including research on the health and environmental impacts of all PFAS chemicals (Senate); listing all PFAS chemicals as a hazardous substance under Superfund (House); and listing PFAS as a toxic pollutant or hazardous substance under the Clean Water Act (House).

Learn more about the letter here.

National Defense Authorization Act

The National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which annually authorizes Department of Defense (DOD) programs, included several PFAS-related provisions because significant PFAS contamination of water supplies has been identified at or around a number of military installations. The enacted version of the fiscal year 2020 NDAA fell short of the initial optimism that the NDAA would include provisions to spark the clean-up of PFAS chemicals across the country under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA or the Superfund statute) and mandate that the EPA establish drinking water standards for PFAS chemicals.

Nonetheless, the legislation included a number of notable PFAS-related provisions. In particular, the legislation (1) phases out the military’s use of firefighting foam containing PFAS chemicals; (2) provides PFAS blood testing to military firefighters; (3) addresses the contamination of water supplies with PFAS from military activities; (4) promotes cooperation on and monitoring of PFAS contamination in water supplies; (5) requires the EPA to take action on PFAS chemicals under the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA); and (6) prohibits the use of PFAS chemicals in military food packaging containers.

Military firefighting foam. Under the bill, the military is prohibited from using firefighting foam containing PFAS chemicals after October 1, 2024 with an exception for use on ships, in emergency responses and in limited testing and training circumstances.

For legacy firefighting foam containing PFAS chemicals, the legislation included a provision similar to a modified version of the PFAS Waste Incineration Ban Act (H.R. 2591). Specifically, all incineration of firefighting foam containing PFAS chemicals must be conducted at a temperature range adequate to break down PFAS chemicals, while also ensuring the maximum degree of reduction in emission of PFAS chemicals; all incineration must be conducted in accordance with the Clean Air Act and at a facility that has been permitted to receive waste regulated under the Solid Waste Disposal Act. Any PFAS-containing materials designated for disposal must be stored in accordance with title 40, part 264 of the Code of Federal Regulations.

Military blood testing. The Protecting Military Firefighters from PFAS Act (H.R.1863, S. 858) was included in the text of the final bill. The fiscal year 2020 NDAA requires DOD to include blood testing for PFAS chemicals as part of routine physicals for military firefighters.

Water supplies. The Prompt and Fast Action to Stop Damages Act (H.R. 1567, S. 675) was included in the legislation. DOD is authorized to temporarily supply uncontaminated water or treated water to agricultural users whose irrigation water is contaminated with PFAS chemicals from military installations. The Air Force is also authorized to acquire property within the “vicinity of an Air Force base that has shown signs of [PFOA and PFOS] contamination” due to activities on the base.

Cooperation on and monitoring of PFAS contamination in water supplies. A provision similar to the PFAS Accountability Act (H.R. 2626, S. 1372) was included in the fiscal year 2020 NDAA. The DOD, upon the request of a governor of a state, is required to “work expeditiously” on cooperative agreements to address, test, monitor, remove, and remediate PFAS contamination in drinking and surface water or groundwater emanating from DOD activities. Cooperative agreements must require the area subject to such agreements meet or exceed the most stringent state or federal limits that apply to the release of PFAS chemicals.

A modified version of the Senate’s substitute amendment to the PFAS Release Disclosure Act (S. 1507), including the Safe Drinking Water Assistance Act (S. 1251) and the amendment’s provision that is somewhat akin to the PFAS Monitoring Act (H.R. 2800), was included in the DOD authorization bill. The fiscal year 2020 NDAA would create an interagency task force to improve federal coordination on emerging environmental contamination, develop a National Emerging Contaminant Research Initiative to fill in research gaps on emerging contaminants, and create a state assistance program to provide federal assistance to eligible states for the testing and analysis of emerging contaminants.

DOD is also required to seek to enter into agreements with municipalities or municipal drinking water utilities located near military installations to share monitoring data related to PFAS chemicals and other emerging contaminants of concern collected at the military installation. DOD must maintain a publicly available website that provides a clearinghouse for information about the exposure of members of the military, their families and their communities to PFAS chemicals, as well as information on PFAS testing, clean-up and recommended available treatment methodologies.

EPA Action under the Toxic Substances Control Act. The modified version of the substitute amendment to the Senate’s PFAS Release Disclosure Act (S. 1507) requires the EPA to take final action on the agency’s January 2015 proposal to amend a significant new use rule for long-chain PFAS chemicals under TSCA. Additionally, the EPA must promulgate a rule to require any manufacturer that has produced PFAS chemicals since 2011 to maintain records and report on the production of PFAS chemicals under TSCA.

Banning PFAS use in food packaging. Lastly, the final bill banned the use of PFAS chemicals in packaging for military field food rations after October 1, 2021.

The House passed the fiscal year 2020 NDAA on December 11, 2019 and the Senate passed the legislation on December 17, 2019. The president signed the bill into law on December 20, 2019.

DOD is beginning to take steps to implement the fiscal year 2020 NDAA. In March 2020, DOD’s PFAS Task Force published a progress report on its plans to assess more than 600 military installations where PFAS has either been found or released.

Appropriation Bills

On December 16, 2019, House and Senate negotiators released the text of two spending packages for fiscal year 2020, which were both signed into law on December 20, 2019. The two packages included: the domestic priorities appropriations bill and the national security appropriations bill; both of which included some PFAS-related spending provisions.

Funding of EPA PFAS Regulatory Activities. The EPA funding division of the domestic appropriations bill contained several PFAS provisions. The final package included $3 million for the EPA to establish Maximum Contaminant Levels under the SDWA for PFAS chemicals, and $5 million to designate PFAS chemicals as hazardous substances by the EPA under the Superfund statute.

The final funding measure directed the EPA to brief the House and Senate Appropriations Committees within 60 days of enactment of the legislation on the agency’s work under its PFAS Action Plan. The final appropriations bill also included $1 million for PFAS work in drinking water systems; $7 million to address PFAS and other contaminants of emerging concern as states carry out Public Water System Supervision Programs; and $13 million for state-led cleanup and remediation efforts.

Funding for PFAS cleanup on military bases. The final military construction funding measure provided $60 million above the Trump administration’s budget proposal for PFOS and PFOA cleanups. DOD will have to submit a plan within 60 days of enactment of the legislation for spending the additional cleanup funds. The DOD funding division of the national security appropriations bill included $100 million in funding for remediating PFAS contamination near Air Force bases, which have often used firefighting foam containing PFAS chemicals to snuff out fires. Additionally, the bill included $10 million for the CDC to assess the health impacts of exposure to PFOS and PFOA.

Stand-alone PFAS Legislation

The long list of proposed stand-along PFAS legislation divides into four key buckets.

First, several bills attempt to better understand the scope of PFAS contamination and boost research efforts around this issue. Examples include the PFAS Detection Act; the Safe Drinking Water Assistance Act; and the PFAS Right-to-Know Act.

Second, a number of bills would mandate that the EPA set standards for PFAS chemicals within a defined time period and based on current regulatory schemes. For example, the PFAS Action Act would require that the EPA classify PFAS as a “hazardous substance” under Superfund, triggering cleanup responsibilities under the Superfund law. The Protecting Drinking Water from PFAS Act would obligate the EPA to set an enforceable contaminant level under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) within two years. The Toxic PFAS Control Act would amend the Toxic Substances Control Act by prohibiting the manufacture of any new substance that is a PFAS chemical within six months after enactment of the bill.

Third, a handful of other bills, such as the PFAS User Fee Act, would make additional funds available to states and local governments to clean up or otherwise address PFAS contamination.

Fourth, several bills respond to PFAS contamination at over 700 military bases nationwide. These bills include the Prompt and Fast Action to Stop Damages Act that would require the development of a plan to clean up PFOS and PFOA contamination for all irrigation water at or adjacent to a military base. The Veterans Exposed to Toxic PFAS Act would require the Department of Veterans Affairs to provide medical care to veterans and their families who experience diseases, illnesses or conditions associated with PFAS exposure.

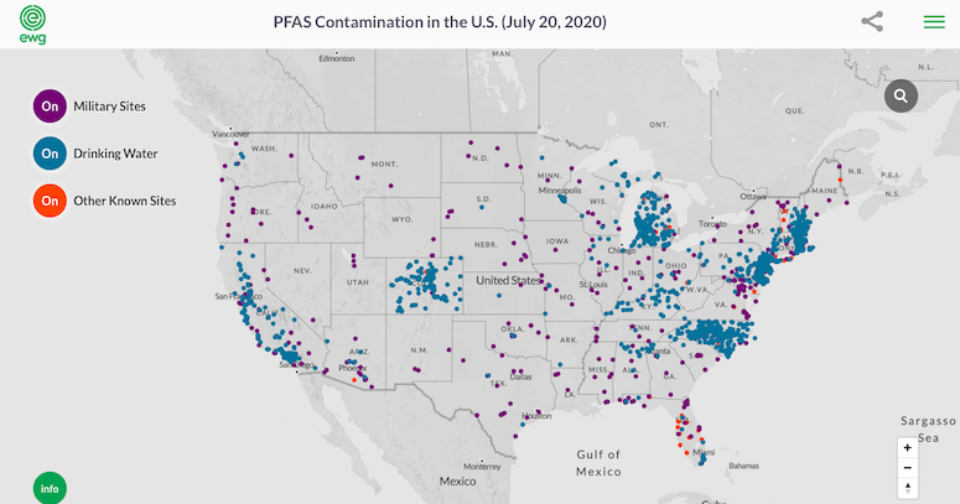

The latest update of an interactive map by EWG and the Social Science Environmental Health Research Institute, at Northeastern University, documents publicly known PFAS pollution in public water systems and military bases, airports, industrial plants and dumps, and firefighter training sites.

Summary of Key Bills

Below is a list of PFAS-related legislation that was introduced in the House or Senate during the 116th Congress (2019-2021).

🔵Enhanced Detection and Research

🔴Proposed Regulatory Mandates

⚪Cleanup Assistance

⚫Response to Military Use of PFAS

🔵 Enhanced Detection and Research

🔵PFAS Detection Act

The PFAS Detection Act (H.R. 1976, S. 950) would require the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) to establish a performance standard for detecting PFAS chemicals in the environment. USGS would also be required to use the performance standard to carry out a nationwide sampling plan to determine the concentration of PFAS chemicals in “estuaries, lakes, streams, springs, wells, wetlands, rivers, aquifers, and soil.” USGS would “first carry out the sampling at sources of drinking water near locations with known or suspected releases” of PFAS chemicals and would consult with states to determine areas that are a priority for sampling. The legislation authorizes $5 million in appropriations to implement the legislation in fiscal year 2020 and $10 million for each fiscal year from 2021 through 2024.

The bill, introduced in the House by Rep. Jack Bergman and Sen. Debbie Stabenow in the Senate, has 22 bipartisan House cosponsors and six bipartisan Senate cosponsors. The Senate Environment and Public Works Committee held a legislative hearing on the PFAS Detection Act on May 22, 2019 and the House Natural Resources Subcommittee on Water, Oceans, and Wildlife held a legislative hearing on the bill on June 13, 2019.

The PFAS Detection Act was included in the substitute amendment to the PFAS Release Disclosure Act, which was approved by the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee on June 19, 2019. The bill was also included in the conference report for the fiscal year 2020 National Defense Authorization Act.

🔵🔴 PFAS Right-to-Know Act

The PFAS Right-to-Know Act (H.R. 2577) would amend the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA) to include PFAS chemicals on the Toxic Release Inventory (TRI). Under EPCRA, facilities that manufacture, process or use at least 1,000 pounds of PFAS chemicals annually would be required to report how much PFAS is released into the environment and/or managed through recycling and treatment. The information submitted by facilities would be compiled into the TRI, which supports decision-making by companies, governments and non-governmental organizations.

Rep. Antonio Delgado introduced the PFAS Right-to-Know Act in the House. A companion bill has not yet been introduced in the Senate. On November 20, 2019, a modified version of H.R. 2577 was included as part of an amendment in the nature of a substitute to the PFAS Action Act (H.R. 535) on the day it passed out of the House Energy and Commerce Committee. The PFAS Action Act was incorporated in H.R. 535, which passed the House on January 10, 2020. The modified version of the PFAS Right-to-Know Act would require the EPA to immediately include an enumerated list of PFAS chemicals on the TRI and would establish a process for adding other PFAS chemicals to the TRI within five years. The reporting threshold would be lowered to 100 pounds.

🔵🔴 PFAS Release Disclosure Act

The Senate Environment and Public Works Committee approved a substitute amendment to the PFAS Release Disclosure Act (S. 1507) on June 19, 2019. As in the original version of the PFAS Release Disclosure Act, the amended version of the legislation would require the EPA to add PFOA and PFOS and any PFAS chemical subject to an existing Significant New Use Rule under the Toxic Substances Control Act to the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act’s Toxic Release Inventory (TRI). Under the TRI, facilities that manufacture, process or use at least 100 pounds annually of PFAS chemicals would be required to report how much PFAS is released into the environment and/or managed through recycling and treatment.

The substitute amendment includes a provision somewhat similar to the Senate version of the Protect Drinking Water from PFAS Act (S. 1473), which would require the EPA to promulgate a national primary drinking water regulation for at least two PFAS chemicals, PFOS and PFOA, within two years. The amended version of the PFAS Release Disclosure Act also includes a provision somewhat akin to the House’s PFAS Monitoring Act (H.R. 2800), amending the Safe Drinking Water Act to require that public water systems monitor PFAS chemicals.

The amended legislation also includes the text of the PFAS Detection Act (S. 950), which would require the U.S. Geological Survey to establish a performance standard for detecting PFAS chemicals in the environment. The bill now also includes a provision nearly identical to the Safe Drinking Water Assistance Act (S. 1251), which, among other steps, would create an interagency task force to improve federal coordination on emerging environmental contamination.

In the title of the legislation labeled “Miscellaneous,” the EPA would be required to promulgate a rule by 2023 that would require any manufacturer that has produced PFAS chemicals since 2006 to maintain records and report on the production of PFAS chemicals under the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA). Additionally, the EPA would be required to take final action on the agency’s January 2015 proposal to amend a significant new use rule for long-chain PFAS chemicals under TSCA.

The PFAS Release Disclosure Act was introduced by Sen. Shelly Moore Capito with two original bipartisan cosponsors in the Senate. There is no companion legislation in the House currently. The legislation was part of the Senate Environment and Public Work Committee’s May 22, 2019 hearing on PFAS legislation. The amended legislation was adopted by the Senate Environment and Public Work Committee on June 19, 2019 and was included as a manager’s amendment to the Senate-passed version of the fiscal year 2020 National Defense Authorization Act on June 27, 2019. A modified version of the substitute amendment without the text of the Protect Drinking Water from PFAS Act (S. 1473) provision and changing the date associated with the TSCA records rule was included in the conference report for the fiscal year 2020 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA).

🔵 Safe Drinking Water Assistance Act

The Safe Drinking Water Assistance Act (H.R. 5361, S.1251) would create an interagency task force to improve federal coordination on emerging environmental contamination, develop a National Emerging Contaminant Research Initiative to fill in research gaps on emerging contaminants, and create a state assistance program to provide federal assistance to eligible states for the testing and analysis of emerging contaminants.

The Safe Drinking Water Assistance Act was introduced in the House by Rep. Lisa Blunt Rochester and has one cosponsor. The bill, introduced by Sen. Jeanne Shaheen in the Senate with two cosponsors, has bipartisan support. The Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works held a legislative hearing to consider the legislation as part of its PFAS-related hearing on May 22, 2019.

The Safe Drinking Water Assistance Act was included in the substitute amendment to the PFAS Release Disclosure Act, which was approved by the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee on June 19, 2019. A modified version of the substitute amendment with the Safe Drinking Water Assistance Act was also included in the conference report for the fiscal year 2020 National Defense Authorization Act.

🔵🔴 PFAS Testing Act

The PFAS Testing Act (H.R. 2608) would require comprehensive toxicity testing of all PFAS chemicals under the Toxic Substances Control Act. All manufacturers and processors of PFAS chemicals would be required to report to the EPA all records of significant adverse reactions to health or the environment alleged to have been caused by PFAS chemicals and all health and safety studies related to PFAS chemicals that the manufacturers and processors are aware of.

Rep. Sean Patrick Maloney introduced H.R. 2608. The bill currently has two cosponsors. There is currently no companion legislation in the Senate. A modified version of H.R. 2608 was incorporated in H.R. 535, which passed the House on January 10, 2020. The modified version of the PFAS Testing Act would require the EPA to mandate by rule, rather than order, comprehensive toxicity testing of all PFAS chemicals and provide for the creation of categories of PFAS chemicals based on hazard characteristics.

🔵🔴 PFAS Monitoring Act

The PFAS Monitoring Act (H.R. 2800) would amend the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) to require that EPA promulgate a regulation that requires within a year of enactment of the legislation that PFAS chemicals be monitored in all public water systems serving at least 10,000 persons. The legislation also includes programs and funding to monitor public water systems that serve populations below 10,000 people. All PFAS monitoring carried out under the bill would be made publicly available online by the EPA.

The legislation was introduced in the House by Rep. Elissa Slotkin and has five bipartisan cosponsors. Companion legislation in the Senate has not yet been introduced. A provision somewhat akin to the PFAS Monitoring Act was included in the substitute amendment to the PFAS Release Disclosure Act, which was approved by the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee on June 19, 2019. The substitute amendment’s provision was also included in the conference report for the fiscal year 2020 National Defense Authorization Act.

🔵 Guaranteeing Equipment Safety for Firefighters Act

The Guaranteeing Equipment Safety for Firefighters Act (H.R. 7560, S. 2525) would authorize the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) to conduct a comprehensive study of personal protective equipment worn by firefighters to determine the prevalence and concentration of PFAS chemicals. The legislation would also establish a federal grant program under NIST to award grants to applicants that submit research proposals to develop safe alternatives to PFAS substances in personal protective equipment.

The bill was introduced in the Senate by Sen. Jeanne Shaheen. It has received bipartisan support from two cosponsors. On November 13, 2019, the Senate Commerce, Science and Transportation Committee voted out of the Committee, an amendment in the nature of the substitute to the bill, which pushed back the post-enactment deadline for completing the study from 90 days to three years. On July 22, 2020, the bill was placed on the Senate legislative calendar and on August 12, 2020, the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation released a committee report on the legislation.

The House’s Guaranteeing Equipment Safety for Firefighters Act includes a three year deadline for completing the study and, authorizes $2.5 million in each of fiscal years 2021 and 2022 to undertake the study, while providing $5 million in each of fiscal year 2023 through fiscal year 2025 to carry out the legislation’s grant program. The bill was introduced in the House by Rep. Ed Perlmutter and has one cosponsor.

🔵 Federal PFAS Research Evaluation Act

The Federal PFAS Research Evaluation Act (H.R. 7348) would require the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in consultation with the Director of the National Science Foundation, the Secretary of Defense and the Director of the National Institutes of Health to enter into an agreement with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine to conduct a study an submit a report to better understand the research and development needed to advance the understanding of the extent and implications of environmental contamination by PFAS, how to manage and treat such contamination, and the development of safe alternatives. The report will be submitted to Congress and 180 days after submission of the report to Congress, the Director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy will submit to Congress an implementation plan for federal PFAS research, development and demonstration activities. The bill has been introduced in the House by Rep. Lizzie Fletcher and has two cosponsors; there is no companion legislation in the Senate.

🔵 Physician Education on PFAS Health Impacts Act

The Physician Education on PFAS Health Impacts Act (S. 4313) would establish an HHS grant program to inform physicians and other medical practitioners about the impact of PFAS chemicals exposure on health outcomes and best practices for patients who have been exposed to such chemicals. The bill would authorize $500,000 in each of fiscal years 2021 through 2025 to implement the legislation.

Each grant recipient would be required to report annually to HHS on training materials developed through use of funds awarded under the grant, including any findings or recommendations that the grantees have determined should be included in physician or medical practitioner training. HHS would then have 90 days to disseminate to the public a summary of findings and recommendations that are included in the provided material.

The bill was introduced in the Senate by Sen. Jeanne Shaheen and has one cosponsor. There is no companion legislation in the House.

🔵🔴⚫ Protecting Firefighters from PFAS Act

The Protecting Firefighters from PFAS Act (H.R. 7687) is composed of two previously introduced pieces of legislation and is intended to provide assistance to firefighters exposed to PFAS chemicals.

The bill includes a provision similar to the Guaranteeing Equipment Safety for Firefighters Act (H.R. 7560, S. 2525), which would authorize the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) to conduct a comprehensive study of personal protective equipment (PPE) worn by firefighters to determine the prevalence and concentration of PFAS chemicals and establish a NIST grant program to fund research proposals for the development of safe alternatives to PFAS chemicals in PPE.

The legislation also includes a provision similar to the Veterans Exposed to Toxic PFAS Act (VET PFAS Act) (H.R. 2102, S. 1023). The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) would be required to provide medical care to civilian firefighters and veterans and their families who experience diseases, illnesses or conditions associated with exposure to PFOA and other PFAS chemicals. The VA would be required to provide medical coverage for illnesses or conditions related to PFAS exposure even if there is insufficient medical evidence to connect the condition to military or civilian firefighter service or residence at a military installation.

The Protecting Firefighters from PFAS Act was introduced in the House by Rep. Daniel Kildee and has two cosponsors. Companion legislation has not been introduced in the Senate.

🔵 PFAS Interagency Research Coordination Strategy Act

The PFAS Interagency Research Coordination Strategy Act (PIRCS Act) (H.R. 7931) would establish a federal interagency working group, housed within the Office of Science and Technology Policy, to coordinate federal research and development needed to address PFAS chemicals. The working group would also be responsible for developing a strategic plan for federal PFAS research and development, including identifying scientific and technological challenges that must be addressed to understand and significantly reduce the environmental and human health impacts of PFAS chemicals and to identify cost-effective, safer and environmentally friendly PFAS alternatives; PFAS removal methods; and PFAS destruction methods. The interagency working group would be required to consult with states and tribes and other stakeholders in developing the strategic plan.

The PIRCS Act was introduced in the House by Rep. Chrissy Houlahan and has three cosponsors. A companion bill has not yet been introduced in the Senate.

🔴 Proposed Regulatory Mandates

🔴🔵⚪⚫ PFAS Action Act (House Version)

On January 10, 2020, the House passed the PFAS Action Act (H.R. 535), which includes many important PFAS provisions and programs. Originally introduced by Rep. Debbie Dingell in the House, the PFAS Action Act would require the EPA to designate PFOA and PFOS chemicals as “hazardous substances” under CERCLA or the Superfund law within one year of enactment of the legislation. Within five years of enactment of the legislation, the agency would have to determine whether to designate all other PFAS chemicals as hazardous substances and post on its website its determination within 60 days of its final decision.

Superfund imposes liability on responsible parties for response costs incurred in the cleanup of sites contaminated with hazardous substances. Designating PFOA and PFOS and other PFAS chemicals as “hazardous substances” would likely trigger cleanups of contaminated groundwater under the Superfund law. Five years after the enactment of the legislation, the EPA would be required submit to the House Energy and Commerce Committee and the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee a report reviewing the actions taken by the agency to cleanup PFOS and PFOA chemicals designated as hazardous substances under the Superfund legislation.

An amended version of H.R. 2566 (the bill has no short title) was included in the PFAS Action Act. EPA would be required within a year of enactment of the legislation to revise the Safer Choice Standard of the Safer Choice Program to include that any pot, pan, cooking utensil, carpets, rugs, clothing, upholstered furniture, stain resistant, water resistant, or grease resistant coating that are not subject to section 409 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act not contain any PFAS chemicals in order to receive a Safer Choice label. The Safer Choice label assists consumers in identifying products with safer chemical ingredients.

The bill also includes several provisions intended to address the risks, particularly health risks, of using firefighting foam containing PFAS chemicals. First, an amended version of H.R. 2638 (no title) was included in the PFAS Action Act. The PFAS Action Act would require the EPA to issue guidance for firefighters and other first responders to minimize the use of foam and other firefighting materials containing PFAS in order to minimize health risks from PFAS exposure. Under this provision, the agency in consultation with the U.S. Fire Administration must submit a report to Congress, with recommendations for congressional action, on the effectiveness of the guidance issued by the agency to minimize firefighters’ and other first responders’ health risks from PFAS exposure. Second, the EPA would be required in consultation with the U.S. Fire Administration to report to Congress on the efforts of the agency and other relevant federal departments to identify viable alternatives to the use of firefighting foam and related equipment containing PFAS chemicals. Lastly, the Federal Aviation Administration and local fire departments are to be included in discussions about the risks posed by using PFAS in foam for aviation hangers.

The PFAS Action Act also includes an amended version of the Providing Financial Assistance for Safe Drinking Water Act (H.R. 2533), which would amend the Safe Drinking Water Act by authorizing until 2024 a $125 million annual grant program for community water systems affected by the presence of PFAS chemicals. Communities included in this program would include communities affected by contamination by GenX, a type of PFAS chemical, and communities in which climate change, pollution, or environmental destruction have exacerbated systemic racial, regional, social, environmental and economic injustices. The grants would help pay for capital costs associated with the implementation of eligible treatment technologies, where current technology is not sufficient to remove all detectable amounts of PFAS chemicals in the community water system.

A provision similar to the PROTECT Act (H.R. 2605) was also included in the House-passed version of the PFAS Action Act. The provision would require the EPA to issue a final rule within 180 days of enactment of the legislation to list PFOS and PFOA as hazardous air pollutants under the Clean Air Act and, within five years of enactment of the legislation, to determine whether other PFAS chemicals should be listed as hazardous air pollutants under the Clean Air Act.

The following pieces of stand-alone PFAS legislation (discussed in more detail below) were incorporated into the PFAS Action Act before it passed the House in January 2020:

- The Protect Drinking Water from PFAS Act (H.R. 2377)

- The PFAS Right-to-Know Act (H.R. 2577)

- PFAS Safe Disposal Act (H.R. 5550)

- Protecting Communities from New PFAS Act (H.R. 2596)

- Toxic PFAS Control Act (H.R. 2600)

- PFAS Testing Act (H.R. 2608)

- PFAS Accountability Act (H.R. 2626; S. 1372)

- The Clean Water Standards for PFAS Act (House Version) (H.R. 5539 version)

- The PFAS Transparency Act (House Version) (H.R. 5540)

The PFAS Action Act would also require the EPA to investigate methods and means to prevent contamination of surface waters, including drinking water, by GenX. The EPA would also have to develop a risk communication strategy to inform the public about the hazards or potential hazards of PFAS chemicals by disseminating information about the risks or potential risks of such substances in land, air, water and products; and notifying the public about exposure pathways and mitigation measures through outreach and education resources. Lastly, U.S. territories would be eligible to receive Safe Drinking Water Act funding for the purpose of addressing emerging contaminants with a focus on PFAS chemicals.

🔴🔵⚪⚫ PFAS Action Act (Senate Version)

The Senate version of the PFAS Action Act (S. 638) would require the EPA to designate PFAS chemicals as hazardous substances under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA or “Superfund”) within one year of enactment of the legislation. Superfund imposes liability on responsible parties for response costs incurred in the cleanup of sites contaminated with hazardous substances. Designating the family of PFAS chemicals as “hazardous substances” would likely trigger cleanups of contaminated groundwater under the Superfund law.

The legislation, introduced by Sen. Tom Carper in the Senate, has 52 bipartisan cosponsors in the Senate. The Senate Environment and Public Works Committee held a legislative hearing on the legislation on May 22, 2019.

🔴 Protect Drinking Water from PFAS Act (House Version)

Similar to the Senate version of the identically named bill, the House’s Protect Drinking Water from PFAS Act (H.R. 2377) would amend the Safe Drinking Water Act by requiring that the EPA publish a maximum contaminant level goal (MCLG) and a national primary drinking water regulation for PFAS chemicals within two years of enactment of the bill.

The MCLG is a drinking water contamination level at which no known or anticipated adverse human health effects will occur and which “allows an adequate margin of safety.” The national primary drinking water regulation includes a maximum contaminant level, which specifies a maximum contaminant level in drinking water that “is as close to the [MCLG] as is feasible” and is an enforceable standard.

The bill was introduced in the House by Rep. Boyle Brendan and has 32 bipartisan cosponsors. A modified version of H.R. 2377 was included in H.R. 535, which passed the House on January 10, 2020. The modified Protect Drinking Water from PFAS Act would require the EPA to promulgate a national primary drinking water regulation for PFOA and PFOS within two years of enactment of the bill and would establish a separate procedure on a different timeline for establishing a national primary drinking water regulation for other PFAS chemicals.

🔴 Protect Drinking Water from PFAS Act (Senate Version)

Like the House legislation of the same name, the Senate’s Protect Drinking Water from PFAS Act (S. 1473) would require the EPA to set a maximum contaminant level (MCL) and a primary national drinking water regulation for PFAS within two years of enactment of the bill. MCLs are health-based standards the EPA sets for drinking water quality under the Safe Drinking Water Act that place an enforceable limit on the level of a contaminant that is permitted in public drinking water systems. This bill would group all PFAS chemicals under one maximum contaminant level. Unlike H.R. 2377, the Senate legislation instructs EPA to consider options for tailoring monitoring requirements under the national primary drinking water regulation for PFAS chemicals for public water systems that do not detect, or are reliably and consistently below the MCL for, those chemicals.

S. 1473 was introduced by Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand in the Senate and enjoys bipartisan support from five cosponsors. The Senate Environment and Public Works Committee held a legislative hearing on the legislation on May 22, 2019.

🔴🔵 PFAS Waste Incineration Ban Act

The PFAS Waste Incineration Ban Act (H.R. 2591) would amend the Solid Waste Disposal Act by requiring the EPA to promulgate regulations prohibiting the disposal by incineration of firefighting foam containing PFAS within six months of enactment of the bill. The prohibition would take effect no later than nine months after enactment of the legislation. Twelve months after enactment of the legislation, the EPA would be required to promulgate regulations identifying additional wastes containing PFAS for which a prohibition on incineration “may be necessary” to protect human health and the environment.

The legislation was introduced by Rep. Ro Khanna in the House with eight cosponsors. There currently is no companion legislation in the Senate. On November 20, 2019, a modified version of H.R. 2591 was included as part of an amendment in the nature of a substitute to the PFAS Action Act (H.R. 535) on the day it passed out of the House Energy and Commerce Committee. The modified PFAS Waste Incineration Act would require the EPA, within six months of enactment of the legislation, to issue regulations requiring that materials containing PFAS chemicals or firefighting foam containing PFAS chemicals are disposed of, such that incineration is conducted in a manner that eliminates PFAS chemicals and that minimizes PFAS chemicals emitted into the air.

A still slightly modified version of the PFAS Waste Incineration Ban Act was included in the conference report for the fiscal year 2020 National Defense Authorization Act.

🔴 Toxic PFAS Control Act

The Toxic PFAS Control Act (H.R. 2600) would amend the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) by prohibiting, within six months after the enactment of the bill, the manufacture of any new substance that is a PFAS chemical and prohibiting the manufacture or processing of any PFAS chemical for a use that is a significant new use under TSCA. Two years after enactment of the legislation, the manufacture of any PFAS chemical for existing uses would be prohibited and three years after enactment of the legislation, the processing or distribution in commerce of any PFAS chemical would be fully prohibited. Further, the EPA would be required to promulgate a rule that (i) prescribes the manner or method of disposal of any PFAS chemical by a manufacturer or processor or by any other person who uses or disposes any PFAS chemical; and (ii) requires each person subject to the rule to notify each state in which a required disposal would take place.

The Toxic PFAS Control Act was introduced by Rep. Madeleine Dean in the House and the bill has six cosponsors. A modified version of H.R. 2600 was included in H.R. 535, which passed the House on January 10, 2020.

🔴 Prevent Release of Toxic Emissions, Contamination and Transfer Act

The Prevent Release of Toxics Emissions, Contamination, and Transfer (PROTECT) Act (H.R. 2605) would require the EPA to issue a final rule adding as a class all PFAS chemicals with at least one fully fluorinated carbon atom to the list of hazardous air pollutants under section 112(b) of the Clean Air Act. One year after the final rule is issued, the EPA would be required to revise the list under section 112(c)(1) of the Clean Air Act to include categories and subcategories of major sources and area sources of PFAS chemicals listed pursuant to the final rule.

Under the Clean Air Act, the EPA is required to regulate pollutants listed as hazardous air pollutants under section 112(b) by establishing emission reduction standards for each category or subcategory of major sources and area sources of listed pollutants.

The PROTECT Act was introduced in the House by Rep. Haley Stevens and has eight cosponsors. A companion bill has not yet been introduced in the Senate. A modified version of H.R. 2605 was included in H.R. 535, which passed the House on January 10, 2010.

The as-passed language require the EPA to issue a final rule within 180 days of enactment of the legislation to list PFOS and PFOA as hazardous air pollutants under the Clean Air Act. Additionally, within five years of enactment of the legislation, the agency must determine whether other PFAS chemicals should be listed as hazardous air pollutants under the Clean Air Act.

🔴 Protecting Communities from New PFAS Act

The Protecting Communities from New PFAS Act (H.R. 2596) would amend the Toxic Substances Control Act by instructing the EPA to determine that any PFAS chemical, for which a notice of intent to manufacture or process has been submitted to the EPA, presents an unreasonable risk of injury to health or the environment. The EPA would then be required to issue an order that prohibits the manufacture, processing and distribution in commerce of such PFAS chemicals.

The legislation was introduced in the House by Rep. Anne Kuster and has one cosponsor. A companion bill has not yet been introduced in the Senate. A modified version of H.R. 2596 was included in H.R. 535, which passed by the House on January 10, 2020. The amended Toxic PFAS Control Act would modify TSCA by instructing the EPA, for a period of five years, to determine that any PFAS chemical, for which a notice of intent to manufacture or process has been submitted to the EPA, presents an unreasonable risk of injury to health or the environment.

🔴 H.R. 2638

H.R. 2638 (the bill has no short title) would require the EPA to issue guidance for firefighters and other first responders to minimize the use of foam and other firefighting materials containing PFAS in order to minimize their health risk from PFAS exposure. H.R. 2638 was introduced by Rep. Lizzie Fletcher in the House. The bill currently has two cosponsors and there is currently no companion legislation in the Senate.

A modified version of H.R. 2638 was included in H.R. 535, which was passed by the House on January 10, 2010. As set forth in H.R. 535, the EPA, in consultation with the U.S. Fire Administration, must submit a report to Congress – with recommendations for congressional action – on the effectiveness of the guidance issued by the agency to minimize firefighters’ and other first responders’ health risk from PFAS exposure.

🔴 Keep Food Containers Safe from PFAS Act

The Keep Food Containers Safe from PFAS Act (H.R. 2827) would require the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to ban the use of PFAS chemicals in food containers and cookware. The FDA would be required to deem any PFAS chemicals “used as a food contact substance” as “unsafe” under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act by January 1, 2022, which would allow the FDA to ban the use of products containing PFAS chemicals that come in contact with food. PFAS chemicals are frequently used to greaseproof, waterproof, and give nonstick properties to food containers and cookware.

The legislation was introduced by Rep. Debbie Dingell in the House and has one cosponsor. There is no current companion legislation in the Senate.

🔴 H.R. 2566

H.R. 2566 (the bill has no short title) would require the EPA within a year of enactment of the legislation to revise the Safer Choice Standard of the Safer Choice Program to include that any pot, pan or cooking utensil not contain any PFAS chemicals in order to receive a Safer Choice label. The Safer Choice label assists consumers in identifying products with safer chemical ingredients.

The bill was introduced in the House by Rep. Darren Soto and has two cosponsors; there is no companion legislation in the Senate. A modified version of H.R. 2566 was included in H.R. 535, which was passed by the House on January 10, 2010.

As set forth in H.R. 535, the Safer Choice label program included original language from H.R. 2566 and, in addition, the program was extended to include labels for carpets, rugs, clothing and upholstered furniture that do not contain PFAS chemicals, and to include labels for stain resistant, water resistant, or grease resistant coating that are not subject to section 409 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act that do not contain PFAS chemicals.

🔴 Protecting Firefighters from Adverse Substances Act

The Protecting Firefighters from Adverse Substances Act (S.2353) would require the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) in consultation with other relevant agencies to develop and publish guidance for firefighters and other emergency response personnel on training, educational programs, and best practices to reduce exposure to PFAS chemicals from firefighting foam and personal protective equipment. FEMA would also be required to develop guidance on limiting or preventing the release of PFAS chemical from firefighting foam into the environment and on alternative foams and personal protective equipment that do not contain PFAS chemicals. FEMA is also to review, and if appropriate, update the guidance three years after the release of the original guidance and every two years after.

The bill, which was introduced in the Senate by Sen. Gary Peters, has 18 bipartisan cosponsors. The legislation passed out of the Senate Homeland Security and Government Affairs Committee on November 6, 2019. Companion legislation has not yet been introduced in the House.

🔴 Water Justice Act

The Water Justice Act (H.R. 4033, S. 2466) is comprehensive legislation intended to ensure that the nation’s water supply is “safe, affordable and sustainable.” One of the provisions in the bill would require the EPA to promulgate an interim national primary drinking water regulation under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) for PFAS chemicals for which the EPA has established a health advisory or toxicity value within two years of enactment of the legislation. The EPA would also be required to promulgate an interim primary drinking water regulation for PFAS chemicals for which the agency has not established a health advisory or toxicity value within four years of enactment of the legislation. The interim regulation would place limits on PFAS chemical levels in drinking water that would be protective of the health of vulnerable populations, including pregnant women, infants and children; and would be as stringent as feasible.

The bill was introduced in the House by Rep. Daniel Kildee and in the Senate by Sen. Kamala Harris with one House cosponsor.

🔴 Clean Water Standards for PFAS Act (House Version)

The House’s version of the Clean Water Standards for PFAS Act (H.R. 3616) would have required the EPA to list PFAS chemicals as toxic pollutants under the Clean Water Act. Additionally, the agency would have to establish water pollution control standards for PFAS chemicals and promulgate pretreatment standards for PFAS chemicals under the Clean Water Act. The bill was introduced by Rep. Chris Pappas in the House and has three cosponsors.

Rep. Pappas introduced a new version of the Clean Water Standards for PFAS Act (H.R. 5539) in January 2020, which was then folded into H.R. 535 and passed by the House on January 10, 2010. The provisions would require the EPA, for each measureable PFAS chemical for which it decides to list as a toxic pollutant under the Clean Water Act, to initiate a process for adding the chemical to the list. The agency would also be required to establish effluent limitations and pretreatment standards for each measurable PFAS chemical, if the EPA has decided to establish such effluent limitations and pretreatment standards. The EPA would also have to publish human health water quality criteria standards for measurable PFAS chemicals that do not currently have criteria standards. The legislation would establish a $100 million grant program to provide grants in amounts not to exceed $100,000 to owners and operators of publicly owned sewer treatment works to be used for the implementation of pretreatment standards. H.R. 5539 has 14 House cosponsors.

🔴 Clean Water Standards for PFAS Act (Senate Version)

The Senate version of the Clean Water Standards for PFAS Act (S. 2980) would require the EPA to establish effluent limitations and pretreatments standards under the Clean Water Act for the discharge of measurable PFAS chemicals from classes and categories of point sources. Within four years of enactment of the legislation, the EPA must publish a final rule establishing for PFOS and PFOA effluent limitations and pretreatment standards for each priority industry category (organic chemicals, plastics and synthetic fibers; pulp, paper and paperboard; and textile mills).

The bill was introduced in the Senate by Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand and has eight cosponsors.

🔴 PFAS Transparency Act

The PFAS Transparency Act (H.R. 5540) would make it unlawful for an owner or operator of an industrial source to introduce PFAS chemicals into a sewer treatment system without notifying the sewer treatment owner or operator. The industrial source owner or operator would have to notify the sewage treatment owner or operator of the identity and quantity of the PFAS chemical; whether the PFAS chemical is susceptible to treatment by sewage treatment; and whether the PFAS chemical would interfere with the operation of the sewage system.

The PFAS Transparency Act was introduced in the House by Rep. Antonio Delgado and has 10 cosponsors; currently there is no companion legislation in the Senate. The text of the PFAS Transparency Act was included in H.R. 535, which passed the House on January 10, 2020.

🔴⚪ Prevent Future American Sickness Act

The Prevent Future American Sickness (PFAS) Act (S. 3227) would require the EPA to designate PFAS compounds as hazardous substances under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (Superfund) and provide grants to households and communities to safely filter PFAS contaminants from their drinking water and assist in the development of water infrastructure. The bill would also prohibit the use of PFAS in food packaging and containers and ban waste incineration of PFAS firefighting foam.

The legislation was introduced by Sen. Bernard Sanders in the Senate and has two cosponsors. There is no current companion legislation in the House.

🔴 Drinking Water Infrastructure Act

The Drinking Water Infrastructure Act of 2020 (S. 3590) would reauthorize Safe Drinking Water Act programs geared towards supporting drinking water infrastructure and providing the technical support and resources needed particularly by “small, rural, and disadvantaged” communities. Further, the Drinking Water Infrastructure Act would require the Environmental Protection Agency to promulgate national primary drinking water regulations for PFOA and PFOS. The bill was introduced by Sen. John Barrasso in the Senate and has three bipartisan cosponsors. The bill passed out of the Senate Committee on the Environment and Public Works on May 11, 2020. A companion bill has not been introduced in the House.

🔴 Break Free from Plastic Pollution Act

The Break Free from Plastic Pollution Act (S. 3944, H.R. 5845) is comprehensive legislation designed to phase out single-use plastic products and take other actions to reduce waste of plastic products. The bill would define PFAS chemicals as a toxic substance. It also would encourage producers of products covered under the legislation to consider eliminating the use of toxic substances in their products and would prohibit the export of plastic products that are contaminated with toxic substances, including PFAS chemicals The bill was introduced in the Senate by Sen. Tom Udall and currently has no cosponsors and was introduced in the House by Rep. Alan Lowenthal and has 91 cosponsors.

⚪ Cleanup Assistance

⚪ Water Affordability, Transparency, Equity, and Reliability Act

The Water Affordability, Transparency, Equity, and Reliability Act (H.R. 1417, S. 611) (WATER Act) would create or amend several drinking water programs. Among many different provisions, the bill would establish a WATER trust fund in the U.S. Treasury and authorize nearly $35 billion in annual appropriations for the fund. 43.5 percent of appropriated funds would be dedicated to the Safe Drinking Water Act’s state revolving loan fund program. The state revolving loan fund program would then be allowed to provide assistance to “publicly owned, operated and managed community water systems for the purpose of updating a treatment plan or switching [its] water sources” due to PFAS contamination.

The bill, introduced by Reps. Brenda Lawrence and Ro Khanna in the House and Sens. Bernard Sanders and Jeff Merkley in the Senate, has 87 House cosponsors and three Senate cosponsors.

⚪ PFAS User Free Act

The PFAS User Fee Act (H.R. 2570) would establish a PFAS Treatment Trust Fund in the U.S. Treasury to make grants to pay for the operation and maintenance costs associated with the removal of PFAS from community water systems and treatment works. The Trust Fund would be financed through an EPA-administered fee on PFAS manufacturers designed to raise at least $2 billion per year and sufficient to cover at least 25 percent of the operation and maintenance costs associated with PFAS removal at community water systems and treatment works. Grants to disadvantaged communities would be prioritized.

The PFAS User Fee Act was introduced in the House by Rep. Harley Rouda and has five cosponsors. A companion bill has not yet been introduced in the Senate. The PFAS User Fee Act was a subject of the House Energy and Commerce Committee legislative hearing on May 15, 2019.

⚪ Providing Financial Assistance for Safe Drinking Water Act

The Providing Financial Assistance for Safe Drinking Water Act (H.R. 2533) would amend the Safe Drinking Water Act by establishing a $500 million annual grant program for community water systems affected by the presence of PFAS chemicals. The grants would help pay for capital costs associated with the implementation of eligible treatment technologies, where current technology is not sufficient to remove all detectable amounts of PFAS chemicals in the community water system.

The bill was introduced by Rep. Frank Pallone, who is chairman of the Energy and Commerce Committee and has six cosponsors. Currently, there is no companion legislation in the Senate. A modified version of H.R. 2533 was included in H.R. 535 when it passed the House on January 10, 2020.

As set out in H.R. 535, annual grant funding was set at $125 million until 2024. Additionally, communities affected by contamination by GenX, a type of PFAS chemical, qualify for the annual grant program and program eligibility was expanded to include communities in which climate change, pollution, or environmental destruction have exacerbated systemic racial, regional, social, environmental and economic injustices.

A nearly identical version of the Providing Financial Assistance for Safe Drinking Water Act was included in the Moving Forward Act (H.R. 2) when it passed the House on July 1, 2020.

⚪ Leading Infrastructure for Tomorrow’s America Act

The Leading Infrastructure for Tomorrow’s America (LIFT America) Act (H.R. 2741) is legislation that would authorize investments in the country’s infrastructure. The LIFT America Act includes the text of the Providing Financial Assistance for Safe Drinking Water Act, which would amend the Safe Drinking Water Act to establish a $500 million annual grant program for community water systems affected by the presence of PFAS chemicals.

The LIFT America Act was introduced in the House by House Energy and Commerce Committee Chairman Frank Pallone and has 44 cosponsors. Currently, there is no companion legislation in the Senate. The House Energy and Commerce Committee held a legislative hearing on the LIFT America Act on May 22, 2019.

⚪ Green New Deal for Public Housing Act

The Green New Deal for Public Housing Act (H.R. 5185, S. 2876) is a multi-provisional piece of legislation that focuses on public housing and related environmental programs. One of the provisions of the bill includes the establishment of a grant program for water quality upgrades and the replacement of water pipes in public housing, if a drinking water quality test reveals combined concentrations of five enumerated PFAS chemicals in public housing that exceeds 20 parts per trillion.

The bill was introduced in the Senate by Sen. Bernard Sanders and has three cosponsors. The legislation was introduced in the House by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and has 26 cosponsors.

⚪ Affordable Safe Drinking Water Act of 2019

The Affordable Safe Drinking Water Act of 2019 (H.R. 5513, S. 3160) would provide states with more tools to mitigate water infrastructure costs through the State Revolving Funds (SRF) program under the Safe Drinking Water Act. States would be able to use SRF funding to install lead and PFAS filtering systems and other lead and PFAS remediation measures across municipal and state facilities. The legislation would amend the Safe Drinking Water Act to allow SRFs to provide funding to remediate lead- or PFAS-contaminated water at public schools, parks, fire stations, police stations, senior centers, community centers, and any other municipal buildings.

The bill, introduced by Rep. Joe Kennedy in the House and Sen. Elizabeth Warren in the Senate, has eight House cosponsors and one Senate cosponsors.

⚪🔵 Moving Forward Act

The Moving Forward Act (H.R. 2) is an omnibus legislative package of $1.5 billion in spending on infrastructure projects. Amongst many provisions the bill includes two noteworthy PFAS-related provisions.

First, the legislation includes a provision similar to the Providing Financial Assistance for Safe Drinking Water Act (H.R. 2533), which would amend the Safe Drinking Water Act by establishing a $500 million annual grant program for community water systems affected by the presence of PFAS chemicals. The grants would help pay for capital costs associated with the implementation of eligible treatment technologies, where current technology is not sufficient to remove all detectable amounts of PFAS chemicals in the community water system.

Second, the bill requires the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to submit a report to Congress on the impact of waters that contain PFAS chemicals on fish that inhabit the waters and are used for recreation or subsistence. The report must include information on the concentration of PFAS chemicals in fish, the health risks posed to persons who frequently consume fish that inhabit waters that contain PFAS chemicals, and the risks to natural predators of fish that inhabit waters that contain PFAS chemicals.

The Moving Forward Act was introduced in the House by Rep. Peter DeFazio and passed the full House on July 1, 2020.

⚪ Providing Financial Assistance to States for Testing and Treatment Act

The Providing Financial Assistance to States for Testing and Treatment Act (S. 3480) would help states remediate PFAS contamination. The legislation would amend the Safe Drinking Water Act to increase funding to $1 billion per year over the next 10 years for a grant program to clean up PFAS contamination. The bill would also amend the Clean Water Act to create a new grant program with over $1 billion per year over the next 10 years to help remediate groundwater contamination from PFOA and PFOS. The Act was introduced in the Senate by Sen. Jeanne Shaheen and has 19 cosponsors; there is no companion legislation in the Senate.

⚫ Response to Military Use of PFAS

⚫🔴 PFAS Accountability Act

The PFAS Accountability Act (H.R. 2626, S. 1372) would hold federal agencies accountable for addressing PFAS contamination at military bases across the country. A federal department, upon the request of a governor of a state, would be required to “work expeditiously” on cooperative agreements to address, test, monitor, remove, and remediate PFAS contamination in drinking and surface water or groundwater emanating from current or past military installations.

A finalized or amended cooperative agreement would require the area subject to the cooperative agreement to meet or exceed the most stringent of state or federal limits on the release of PFAS chemicals. If a cooperative agreement is not acted upon within one year of the governor’s request, the President would be required to submit a report explaining why a cooperative agreement has not been finalized or amended and provide a projected timeline for doing so to Congress.

The PFAS Accountability Act was introduced by Rep. Fred Upton, the former Chairman of the Energy and Commerce Committee, and has four cosponsors. The text of H.R. 2626 was included as part of H.R. 535, which passed the House on January 10, 2020.

A provision similar to the PFAS Accountability Act was included in the conference report for the fiscal year 2020 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). Under the fiscal year 2020 NDAA, a finalized or amended cooperative agreement would require the area subject to the cooperative agreement to meet or exceed the most stringent of state or federal limits on the release of PFAS chemicals.

In the Senate, the PFAS Accountability Act was introduced by Sen. Debbie Stabenow and has 10 cosponsors.

⚫🔴 Prompt and Fast Action to Stop Damages Act

The Prompt and Fast Action to Stop Damages Act (H.R. 1567, S. 675) would authorize the Department of Defense (DOD) to temporarily supply uncontaminated water or treated water to agricultural users whose irrigation water is contaminated with PFAS chemicals from military installations. The Air Force would be authorized to acquire property within the “vicinity of an Air Force base that has shown signs of [PFOA and PFOS] contamination” due to activities on the base. The Air Force would then be required to remediate the contamination. No later than 180 days after enactment of the bill, DOD would be required to submit to Congress a cleanup plan for all water at, or adjacent to, a military base that is contaminated with PFOA or PFOS.

The bill was introduced by the entire New Mexico congressional delegation in both the House and Senate. The Prompt and Fast Action to Stop Damages Act was included in the conference report for the fiscal year 2020 National Defense Authorization Act.

⚫🔴 Protecting Military Firefighters from PFAS Act

The Protecting Military Firefighters from PFAS Act (H.R.1863, S. 858) would require the Department of Defense (DOD) to include blood testing for PFAS chemicals as part of routine physicals for military firefighters. The bill was introduced in the House by Rep. Donald Norcross and has 22 bipartisan cosponsors. The legislation was introduced in the Senate by Sens. Jeanne Shaheen and Lisa Murkowski and has five bipartisan cosponsors in the Senate. The bill was included in the conference report for the fiscal year 2020 National Defense Authorization Act.

⚫🔴 Veterans Exposed to Toxic PFAS Act

The Veterans Exposed to Toxic PFAS Act (VET PFAS Act) (H.R. 2102, S. 1023) would require the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to provide medical care to veterans and their families who experience diseases, illnesses or conditions associated with exposure to PFOA and other PFAS chemicals. The VA would be required to provide medical coverage for illnesses or conditions related to PFAS exposure even if there is insufficient medical evidence to connect the condition to military service. The legislation would make PFAS-exposed veterans eligible for VA disability payments and medical services.

The bill was introduced in the House by Rep. Dan Kildee and has 22 House cosponsors. The VET PFAS Act was introduced in the Senate by Sen. Debbie Stabenow and has two Senate cosponsors.

⚫🔵 PFAS Registry Act

The PFAS Registry Act (H.R. 2195, S. 1105) would require the Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) to establish and maintain a national database for service members and veterans who may have been exposed to PFAS chemicals. The VA would be required to “periodically notify eligible individuals of significant developments in the study and treatment of [health] conditions associated with exposure to PFAS.” Five years after enactment of the legislation and every five years thereafter, the VA — in consultation with the Department of Defense and the EPA — would be required to submit to Congress recommendations for additional chemicals to add to the registry.

The bill was introduced in the House by Rep. Chris Pappas and in the Senate by Sens. Jeanne Shaheen and Mike Rounds, and has 26 bipartisan cosponsors in the House and four bipartisan cosponsors in the Senate.

⚫🔵 PFAS Quantum Evaluation Act

The PFAS Quantum Evaluation Act (S. 1534) would direct the Department of Defense (DOD) to develop best practices for deploying advanced computers to address the risks associated with exposure to PFAS. The legislation was introduced by Sen. Gary Peters in the Senate with Sen. Joni Ernst as an original cosponsor. There is no companion legislation in the House yet.

⚫🔵🔴 Safe Water for Military Families Act

The Safe Water for Military Families Act (H.R. 3226) would require the Department of Defense (DOD) to ensure it only uses non-fluorinated firefighting foam by 2029. Firefighting foam often can be partially composed of fully fluorinated PFAS chemicals. The bill would also require DOD to evaluate and report to Congress on the best practices in the cleanup of ground contaminated by PFAS chemicals; determine the estimated costs of the different types of cleanup methods; and estimate the length of time for various types of cleanup methods.

The legislation was introduced in the House by Rep. Andy Kim and does not yet have any cosponsors. Currently, there is no companion legislation in the Senate.

⚫🔵 Protect Our Military Children Act