Environmental Justice in the Sunshine State

Samantha Blend / July 29, 2022

This piece is part of our Student Blog Series, featuring posts on climate, clean energy, and environmental issues from the State Impact Center’s legal interns and other students working with the Center.

This year has brought increased initiatives and resources at the federal level to help states address Environmental Justice (EJ), as the State Impact Center recently covered in its blog on key developments in EJ.

The next logical question is: what is happening at the state level? This post will focus on a state with a wide range of pressing environmental challenges that disproportionately affect underserved communities: Florida. Three issues at the forefront of Florida’s EJ battle include:

- hazardous waste sites found in underserved neighborhoods including superfund sites and incinerators such as the Doral incinerator,

- the lack of accessible information for linguistically isolated Floridians, and

These issues represent just a portion of Florida’s EJ challenges. EJ work in Florida is typically a community-led effort, and organizations across the state repeatedly address such issues as seen in Earthjustice’s environmental justice work, University of Miami School of Law’s environmental justice clinic’s projects, and The Cleo Institute’s report on a climate-ready future for Florida.

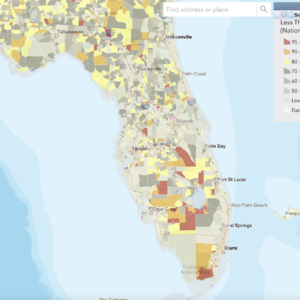

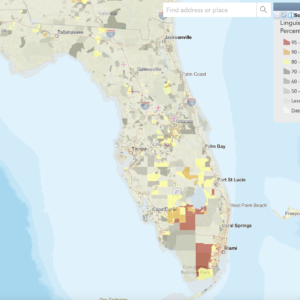

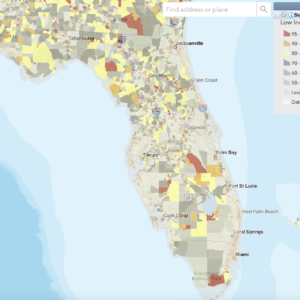

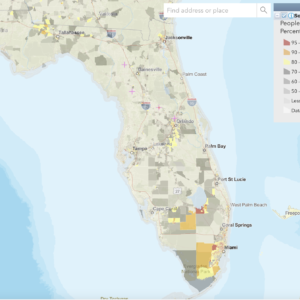

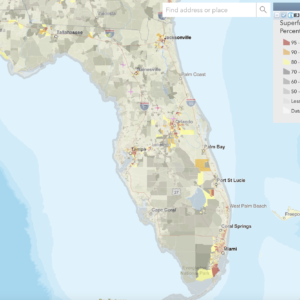

Several maps gathered from the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool help show that there is often overlap between the areas affected by these environmental challenges and at least one socioeconomic factor provided by EPA.

Maps of Florida’s EJ Indicators

These maps of Florida’s EJ indicators were generated through EPA’s EJ Screen tool by selecting the individual socioeconomic indicators available through the tool and limiting the map view to Florida. These four maps focus on the following socioeconomic factors respectively: less than high school education, linguistically isolated, low income, and people of color. Click on an image to enlarge it.

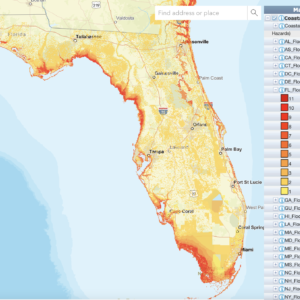

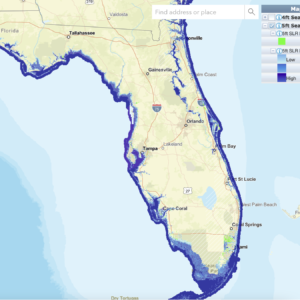

Maps of Florida’s Environmental Challenges

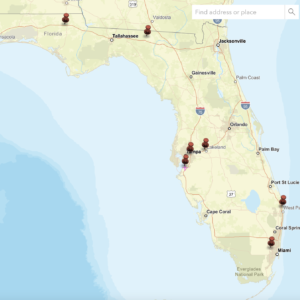

These maps of Florida’s environmental challenges were generated through EPA’s EJ Screen tool by selecting specific environmental justice index and climate change data points available through the tool and limiting the map view to Florida. The first three maps were generated by selecting superfund proximity, coastal flood hazard, and 5ft sea level rise, respectively. The final map was generated by pinning each superfund site that EPA has committed to reviewing the cleanup process for in Florida. Click on an image to enlarge it.

EJ Concerns

Specific examples of these environmental challenges are seen throughout the state. First, 70 percent of Florida’s municipal incinerators are located in communities of color and linguistically isolated communities. In addition, tens of thousands of Central Floridians live near toxic waste sites that are often unmarked, such as the Tower Chemical Company site that used to be a manufacturing site with a waste disposal system that led to contamination of the soil and water.

In South Florida, the Doral incinerator is in a community with 93 percent people of color, 36 percent below the poverty line, and 88.2 percent who speak a language other than English at home. Accounts from the community near the Doral incinerator describe experiencing an unbearable garbage smell that limited the time folks could spend outdoors. It was estimated in Earthjustice’s account of Florida’s Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) permitting process for the Doral incinerator that one third of those attending the public meeting about the incinerator would be Spanish speakers. Yet DEP initially refused to provide a Spanish-language interpreter before finally agreeing to have a bilingual employee provide the gist of the comments in Spanish after multiple requests. Failing to provide adequate translation decreases the equality of such a process by limiting a community’s ability to actively respond to environmental issues that affect their day to day lives.

Finally, climate gentrification poses a risk of displacing underserved communities. There are three ways climate gentrification typically occurs: (1) low-income areas with low climate risk attract wealthy homebuyers that price out existing residents, (2) the high cost of living in an area affected by high climate risk forces out lower-income households, and (3) areas that implemented resilience strategies become more desirable and less accessible for lower-income households. In a recent report on climate displacement in Florida’s coastal communities, researchers examined census blocks within three Florida counties (Duval, Pinellas, and Miami-Dade) and grouped them in terms of high, medium, or low risk of displacement. In each county, the majority of residents in high-risk blocks have less than a bachelor’s degree and at least 19 percent are living below the poverty level. In addition, in the high-risk areas of Duval and Miami-Dade counties, a little over 40 percent of residents are African American.

EJ Activism

Despite these issues affecting residents throughout the state, most state agencies do not obviously incorporate EJ into their work. However, some local and federal agencies are taking EJ action. 17 cities and counties committed to a just transition to 100 percent clean energy through Sierra Club’s Ready for 100 campaign. This campaign worked on dismantling unjust energy systems and getting local leaders to recognize and work against the disproportionate effect of the unequal energy system on underserved communities. In addition, EPA has committed to reviewing cleanups at eight Florida superfund sites.

Local nonprofits and coalitions are also active in advocating for EJ causes. Large organizations like Earthjustice represent grassroots organizations like FL Rising and the Conservancy of Southwest Florida in EJ-focused actions such as a Civil Rights complaint against Florida DEP and a suit against EPA challenging their approval of the state taking over wetlands permitting in Florida to prevent harming Florida’s critical wetlands. This includes Big Cypress National Preserve, where a plan to drill for oil would harm sacred lands of the Miccosukee Tribe. Other organizations at the frontline of these issues include 1000 Friends of Florida and the Cleo Institute.

These victories are important in counteracting environmental injustice in Florida. As these and other EJ issues progress, it is important to keep an eye on how these efforts progress to support all residents of Florida.

Read about how state attorneys general can be prominent partners in the fight for EJ.

This page was updated on February 27, 2024 to better meet our accessibility standards. To see the page as it was initially published, click here.